Beyond The Light of Summer Night – An Essay on Jan-Anders Eriksson’s Art

At the time of his first exhibition in the beginning of the seventies, Jan-Anders Eriksson (commonly known as Jatte), already showed an extraordinary artistic profile, even though he may not have been completely aware of his aims and methods. Naturally, his painting has changed throughout the years but he maintains an unmistakable tone, which is his own.

Jatte belongs to the artists who are able to remain accomplished eclectics – in mind as well as in artistic practice – yet remain faithful to themselves. Somewhere in the creative process lies an inherent necessity, which could be labeled integrity. Uninfluenced by the shifts of trends and changes of the aesthetic fashion, they do as they want and please; pick what they need and don’t give a damn about the rest.

Of course there is history of art behind. Among the first of Jatte’s paintings that I saw were two ”hommages”, one to Ensor and one to Munch. Two self-assured cavilers of conventions who also showed the depth and conflicts of the human soul. It is in the difference between these two that we find the wide scope of Jatte’s artistic touch: irony and emotion, even passion. Not that these approaches necessarily contradict one another but they do create a conflict in Jatte’s art, which is fruitful.

Expressionism, this versatile and individualistic ”ism” is hence one of the sources of

Jatte’s art. Yet another is the popular feature, in spite of the fact that the pictures are relatively difficult to grasp. Considering the fact that Jatte is a connoisseur of jazz who has made several radio programmes about jazz, the idea does make sense. In modern jazz one does find the combination of popular roots and a form of expression which is technically driving, yet at the same time strongly emotional and sensually colored – a form which is Jatte’s, too.

Just like in jazz, there is a permanent undercurrent of the blues present in Jatte’s art, namely melancholy. Add the radicalism, the political potential. Nevertheless, ”people” and ”popularity” are probably two of the most loaded words in modern times. Jatte’s popular features, however, (perhaps one should make a distinction and say ”popular roots”) are light years from the salivating kind of populism of Bert Karlsson’s subhuman kind, to characterize the phenomenon euphemistically. There is an indisputable distance between Charlie Parker and Charlie Mingus on the one hand and pseudofascist hits on the other.

Expressionism originates, as is well known, from Romanticism, in its stress of the artistic subject. Jatte’s intellectual fellowship with Romanticism is accentuated. Jatte’s sensitive feeling for nature and the affection for the genuinely popular is there, but present is also an emotional and existential yearning which in concrete is expressed in the perspective which usually leads further and further away from a secret center hidden in the remote distance. One may come to think of the visionary landscape of Caspar David Friedrich. Jatte undoubtedly feels congenial with the old Romanticist; he has even written a poem about him which clearly contrasts the tourist’s visual exploitation of nature and its grandeur and strength, hidden to civilized man.

Jatte sides with nature even if it ever so of ten appears barren and inhospitable. It is a kind of subject. And Jatte’s art aims at finding the essence behind nature’s various forms of revelation. He does it with affection but also with irony, well aware of the fact that Man ultimately is estranged. Sometimes I see a relationship between Jatte’s paintings and Werner Herzog’s films, particularly with ”Hertz aus Glas”, where the landscape inspired by Friedrich plays a significant part but in which nature’s force – impenetrable to reasoning – affects people in a mysterious way: trance, hypnosis, somnambulism, rite and magic. Precivilized nations have remained in their profound layers. Jatte is also very interested in cultures like the Sami and Amerindian, in Shamanism.

One must not forget, however, that Romanticism is a very much hackneyed and tainted concept. The word itself has become ruthlessly trivialized to such an extent that to many, it is synonymous to a wet-eyed couple in love, sitting with pouting mouths over a sumptuous shellfish dinner which they even forget to taste.

If one thoroughly – and with a somewhat open mind – contemplates Jatte’s pictures, Romanticism suddenly changes meaning. It even becomes the opposite of popular amorous idyll. I have already mentioned the artistic subject as a characteristic feature of Romanticism, a sensitive feeling for nature is another. Romanticism, however, was a revolutionary period, a time of rebellion against Enlightenment and its belief in reason, an upheaval of perception itself and a time when the artist and the poet ranked high at the same time as the subconscious was set free (Freud was actually just a straggler and a philistine systematist who – with 100 years of delay – accounted for and in a comic way of ten misunderstood what was pure truism to poets and artists) and a time where radical as well as conservative ideologies were crystallized. Romanticism is a period of contradiction and alienation,’which contained a sense of brotherhood and individualism. I believe that these opposites form a context ”prone to scuffle” in Jatte’s art which makes it contemporary Romanticism indeed, dedicated and dedicating but with deep rootlets at the same time. Also far beyond Romanticism. There are occasionally ”naive” features in Jatteis art but his painting is neither that of Naivism – which implies borrowed plumes or feigned innocence, nor is it genuinely naive. I do remember, however, that during a visit to the Modern Museum of Art in Stockholm some ten years ago we both gave way to joint admiration of the painting ”Elk and Norwegian Elkhound” (”Älg och Gråhund”) by the singular artist Lim-Johan Olsson from Hälsingland.

Such ”hunting-pieces” belong to third-rate art and to the standard repertory of ”popular” artists with commercial aims. The authenticity of Lim-Johan’s work, however, is unmistakable; a kind of value perspective is established – the hound is as big as the elk, and what is more, the elk is also the prey, whose on ly modest advantage in real elk- hunting is its size and strength. The dog appears to throw itself over the elk like a lion would over a smaller antelope and the elk’s whole appearence – painted by Lim-Johan in dull earthy colors – is characterized by death struggle while it seems to be sinking in some kind of morass. Anguish glows from the wide open eyes. The picture is a memento to those who believe there is a kind of ethical purpose in nature and it shows a view completely antagonistic to the ridiculous macho cult of elk-hunting. There isn’t even a hunter with rifle in sight. Jatte – always inclined to see things from an”underdog perspective” – found something genuine, human as well as artistic, in this peculiar picture: that Lim-Johan, the bullied and very much laughed down ”village idiot”, simply portrayed himself as the elk.

Later on at the pub, Jatte became impassionedly eloquent when speaking about mechanisms of repression in the countryside and we talked for quite a while about the picture, about Lim-Johan and ”naive” art in general while our friends from Uppsala began to look like they believed that our large consumption of beer had a sentimental impact on our discussion and made us both square when discussing our common background from Norrbotten. What actually happened was that they could not digest the fact that our conversation dealt with experiences and feelings which simply did not need an accompanying theory to be valid. It was really about discovering what is genuine. And it is precisely the sense of what is genuine, no matter if it is about art, jazz or people, which I believe is a characteristic of Jatte. He is probably immune to bourgeoisie ”charm”, i.e. its non-committal conversation, its conventions, set of social rules and rigid way of thinking, its hygien ism and taboos which actually only serve the purpose of shutting out an unbearably dirty and violent reality. On a ground of half a bottle of whiskey, placid Jatte is capable of uttering deadly sarcasms about the bourgeoisie. On these occasions he reminds me of a spi ritual ’cousin of Bunuel’s. What is more, he is able to see how the bourgeoisie mechanisms of repression have been transmitted downwards, how self- repression works among the lower classes. Like in the case of Lim-Johan, it is usually sensitive people who are defined as peculiar, deviant, and anti-social, as idiots. If the same people belong to the upper classes they are regarded as eccentric, among the lower classes, however, there is no mercy. This is the meaning of the so-called ”Jante Law”which is a Glass law that does not allow people to feel significant.

Jatte’s ambivalent feelings towards this aspect of popular belief are expressed in a painting with a rather cryptic title,

”Waiting for Arne” (”I väntan på Arne”). Jatte has told me that Arne exists in real life and is an original person living in a secluded house outside Nattavaara. This is probably as far away from so-called civilization as one can get but there is also a deeply tragic human fate present in this ”original”; severe abuse in childhood and a life with repeated visits in mental hospitals. In his own way, Arne has however succeeded in asserting his subject and his sensibility. Compensatory or not, but he has converted his house into a product of the imagination – the exteriör as weil as the interior are covered with peculiar paintings – like a mailman Cheval placed in the sparsely-populated province of Lappland. Jatte is fascinated by such eccentrics, but there is much more than pure identification in Jatte’s painting.

There is waiting and expectation present in the painting as well as in the title, similar to the eager belief in the Second Advent shared by the believers. Particularly Christ could be seen as a metaphor for socially stigmatized Man, a vagabond preacher, speaking of himself as the Son of God, refusing to accept a ltdecent job”, and what is more, he persists in walking on water. In these ”enlightened” times, Christ would hardly be crucified, but at his return, he would run the risk of being saddled with meddlesome psychiatrists and psychologists. If he also defied law and order and was seen in company of harlots, it is not unlikely that the police promptly would offer to lend a hand to get him under lock and key.

It can’t be helped that one finds a relationship between the social eccentrics and Christ. The term ”holy fools” does exist in Russian Orthodox spi ritual ity. This could be regarded as respect, a view apparently shared by Jatte, a kind of purity of the heart, if one prefers. At first sight, Jatte’s painting may give the impression of a color-photo negative; the light emanates from Arne’s house, glowing against a background of cold blue darkness. Even though the house is of a kind that is not uncommon in the countryside, it makes one think of a fairy castle as well as a haunted house, but it is perhaps a synthesis of both. The house has an indisputable identity which may weil be that of Arne. Perhaps the painting is a portrait of him. Fairy creature and ghost? The secret of the house, however, remains hidden. In the sky the re are light phenomena: comets, meteorites or omen. Do they herald Arne’s return? Like always, Jatte prefers to ask questions rather than to give plain answers. When he works he’ uses his intuition, and consequently he trusts the intuition of the viewer. I find it difficult myself to dismiss the picture’s apocalyptic atmosphere. The final judgment foreboded in a house in Nattavaara.

attitude is expressed in another painting titled ”Expedition on the Outskirts”. The title reveals that it deals with the unknown, and when I asked him, Jatte confirmed that the painting was inspired by Andrej Tarkovskij’s sublime film ”Stalker”. I will not go into detail, but the film is about an expedition into something called The Zone, a roped-off area which on the surface appears to be devastated by a cataclysm or the result of a nuclear melt-down (Tarkovskij’s film has by many been seen as a premonition of the disaster at Tjernobyl) , but underneath the surface it is an account of a journey inta a dimension different from Durs, a confrontation with Mystery itself.

Jatte’s painting is characterized by desolation. The buildings in the background seem to have been abandoned long ago, and present in the picture are two figures who both, in some strange way, seem to belong in the landscape and yet, at the same time, they appear to be casual guests. One can not even be certain that the ground they are standing on actually is solid ground. The surface which makecs up the main part of the picture breaks through and reflects the two figures and it appears to be something between soaked asp halt and mud. Dusk reigns the whole scenario which could be interpreted in existential terms. Hades or a secularized Purgatory? Is this what remains of Mystery af ter all expositions and theological treaties? GodIs silence?

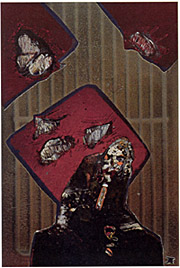

A picture which is even more versatile and apocalyptic is the painting ”Staffan’s Dogs”. An explanation to the title is found by looking in the upper right-hand corner where Jatte has placed some of the dogs from Staffan Hallström’s famous work ”Nobody’s Dogs”. The ironic approach is thus established. In the foreground we find a vaguely human figure with a bird’s head whose glowing eyes glare at the viewer. The dark sky is in a commotion, it seems to forebode disaster. It may remind us of skies as painted by such disparate painters as Albert Pinkham Ryder, Marcus Larsson and Eugene Delacroix, artists who are usually labelled Romanticist.

I would like to regard the painting as ”romantic irony” , maybe even as a camouflaged self-portrait or an initiated comment to artistry. There are clues to Jatte’s picture in Hallström’s painting: the dogs – actually a cross between wolf and dog – are standing with the tails against each other, thus forming a shield against approaching threats. They are both threatened and aggressive and they certainly belong to nobody. Artistry is very much a refuge for those who refuse to be domesticated and at times, artists appear to be a crowd of individualists who stick together only out of necessity against an increasingly unsympathetic and uniform society. A society which in addition, with increasingly pronounced liberal brutality, force more and more people to flock together in order to defend their existence. Hallström, who made his painting in the fifties, probably gave no thought to our approaching social and spiritual atmosphere. A plain political interpretation would indeed be a senseless simplification but Jatte, who naturally is a man with left-wing sympathies, is not unaware of the moral, intellectual and social bankruptcy the bourgeoisie regime is about to produce.

”The birdman” in the foreground, however, is ambiguous. On the one hand he looks like an individualistic anarchist about to provoke chaos, and on the other, he could be an estranged witness who has survived out of sheer spite. A third possibility is that he is a prophet of the kind mentioned in the Old Testament who probably would croak ”Didn’t I say so!”

Anyhow, there are at least three souls present in an artistry of Jatte’s kind. And Jatte does not belong to the gullible crowd of newly-bathed optimists. Artistry also means looking behind veils and smoke screens, to perceive a future still in hibernation, and to stand alone in this activity, to be estranged. All the same, there is irony present – not only in the quotation of Hallström – because the ”birdman” never takes off, he doesn’t even have wings. An Ikaros, earth-bo undout of necessity , is that what the artist is? In the pictures I have described so far, I have verified the prevailing darkness. With only a few exceptions, this is generally true of Jatte’s art.

As is well-known, Norrbotten is usually described with tourist clichEs like ”The land of the Midnight Sun”. This statement, however, is true on ly a few months every year. During winter – which is very long, I assure you – darkness reigns practical ly unrestricted. Jatte’s art exists, figuratively well as literally, beyond the light of summer night which was discovered 100 years ago by members of the Art Society, and since the n it has been illustrated by new generations of artists.

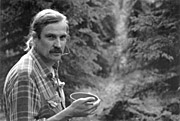

Jatte, however, knows his Norrbotten from the inside. He was born and raised in Södra Harads 100 kilometers north of Luleå by the Lule River. An agricuiturai district where the 17th century still seems to be present. The phone number of his childhood was Harads 2 (the phone number to the shopkeeper on the other side of the river was Harads 1) and he could tell you about vacations designated for scrubbing floors and peeling potatoes at school. He knows of proverbial sayings and linguistic expressions of the same kind that my grandmother, born in 1890, would use incidentally and which are not the vocabulary general ly used by people who are my age. There are only ten years between Jatte and myself but the difference in. experience is that between rural society- and town. But Norrbotten is not only a secluded province. It must be a coincidence with a purpose that Jatte lives only within a stone’s throw of the medieval church of Gammelstad, surrounded by the unique and universally recognized church village. A construction which gives evidence of wealth and social self-confidence among old farmers of Norrbotten: the altarpiece was ordered from a Dutch master, apparently without hesitation. Throughout generations, Provincialism has constantly merged with and confronted incentive from the outside.

Jatte is deeply rooted in a continental expressionist tradition, but he also seeks popular and cultural roots, in fact even roots from pre-civilization. ”Popularity” thus becomes a means of breaking away from the fetters of civilization and conventionality. Socialism – in the unprejudiced and imaginative version of COBRA – is a suitable tool for interior and exterior journeys.

In these ”Postmodern” times, Jatte does not only have the endurance of being expressionist, in his expression of form he also has the courage of being pre-modern in his artistic conception. There is a shorter distance between the caves of Altamira and Jatte than between Jatte and a media-adjusted rascal like Dan Wolgers. There are Dionysus-like features in Jattels art, more or less in the version of Nietzsche. The manifestation is expressed in color, in the artistic ”gesture”. But he has also expressed inebriation in a painting simply called ”Inebriation”.

The picture, however, is hardly a tribute to Bacchus and his gifts. There is not a trace of rapture and euphoria present; the torments of hangover seem to take place alongside intoxication. My experience of drinking-habits in Norrland confirms the idea: somewhat parodic, it could be described as a way of pouring down as much aquavit as quickly as possible, and thereafter to go outside and fall in a snow drift.

This is not a kind of drinking one associates with parties, with social rituals, lark and noise, but rather with melancholy, aggressiveness and anguish on an ascending scale. A kind of home-made psychotherapy. It is essential to get the opportunity of driving away the spi ritual dross that inevitably gathers inside of us. This is probably the intention of the behavior in this area which media refers to as ”The Vodka Strip”.

The male figure in Jatte’s picture – who incidentally has some features in common with Jatte himself – turns his fronting towards the viewer, the re is a consciously aggressive attitude in his posture, but there is also ambivalence, as if he was assailed with demons. But bearing in mind the old Greeks, the demons are also entities representing creativity. According to Dionysus belief, inebriation is a kind of diving-bell, destined for journeys into the deep levels of the soul, perhaps to the point where ”what is cattle in others/is cattle also in you”, to quote Gunnar Ekelöf, one of the poets Jatte recites in long passages by heart, when the spirit moves him.

It may seem like Jatte is a gloomy soul. There is much melancholy in his paintings, and at times even anguish. Socially, however, Jatte is one of the funniest people I have ever met. With unerring precision, he makes just the right comment at the right time. His replies general ly serve as an efficient way of putting much to pretentious people in place. I could examplify with several anecdotes, but the problem is that it is well-nigh impossible to do justice to these situations in writing. I will confine myself to stating that what Jatte does, at times in a cheerful mood, could be called verbal guerilla warfare. Sometimes, his sense of humour is reflected in his painting. On such occasions, it is rarely about biting irony or withering sarcasm, but rather subtlety of a warmer ”temperature”. The painting ,”Put On Your Cap, Lad” is one example. We see two figures – a man and a boy, probably father and son – in a cold red landscape. There is a pronounced physical distance between them, but the man’s abrupt request to the boy, i.e. the title of the painting, reveals a sparing and awkward consideration and tenderness such as it becomes in a reality where the permafrost seems to live within the people. Bitter-sweet or mildly ironic, the picture is a conciliating recall of a childhood that is irrevocably lost. It is easy to recognize oneself.

There is nostalgia in Jatte’s art but of a kind that never recoils upon idealization. He was brought up with the farm land and its values, but he remains critically independent to his heritage. Jatte is more closely related to the hunter and pathfinder, to the vagrant and the vagabond, than to the peasant proprietor, the embryonal capitaiist. Jatte is – with allusion to Hallström’s painting – ”nobody’s dog”.

Staffan Kling

Translation into English by Ulrika Bley. From the Art Magazine Hjärnstorm ( Brainstorm).